By Elazar Abrahams

A few years ago, I wrote a paper for a film class, which follows below. The assignment was a scene analysis, a close read of a piece from any film on the syllabus up till that point. I chose the above shot from Stanley Kubrick’s iconic 2001: A Space Odyssey. After posting a previous write-up of a shot from Singin’ in the Rain that was well-received, I figured why not share more of those types of pieces. Good content is good content.

From silent age classics like Buster Keaton’s Sherlock Jr. (1924) to cartoon farces like Looney Toons’ ‘Duck Amuck’ (1953), film has always been a visual medium, excelling in telling stories without dialogue. Without a single word being spoken we know exactly what is happening on screen. It’s in the framing, it’s in the timing, and the visuals. Even as Hollywood moved to “talkies,” communicating ideas without the use of words arguably remains the foundation of cinema. Legendary director Alfred Hitchcock – of Rear Window (1954) and Vertigo (1958) fame – said it best when he lamented that many films from his era were just moving “photographs of people talking.” When we “tell a story in cinema,” he mused, “we should resort to dialogue only when it’s impossible to do otherwise.” The 1968 science-fiction epic 2001: A Space Odyssey is the perfect example of how to do so. The film is a masterclass in frames, shots, and scenes ‘showing, but not telling.’

In a New York Times interview promoting Space Odyssey, its auteur director Stanley Kubrick is quoted as saying “there are certain areas of feeling and reality—or unreality or innermost yearning, whatever you want to call it—which are notably inaccessible to words.” The utter lack of dialogue for much of 2001’s runtime is certainly unconventional, but Kubrick understood that the way to truly reach viewers deepest emotions was to utilize the non-verbal elements that film allows for.

This style is apparent right from the film’s lengthy opening scene. After a fade-in, we see a wide shot of a landscape at sunrise. The words “THE DAWN OF MAN” appear on the lower portion of the frame and then fade away. We hear the sounds of nature – insects chirping, wind blowing, and birds chirping. It’s a stark contrast to what came just before: the black screen MGM logo and the opening credits with a bombastic score drumming loudly.

For the next minute and forty seconds, Kubrick shows us ten distinct still shots of the landscape and location. Within frame, we see nothing living. The expanse stretches off into the distance, scattered with rocks and weeds. Then, the next two shots clearly bring animal bones into focus. This is followed by the introduction of the ape-men and a few live animals living amongst them. In line with the movie’s theme of humanity’s evolution, Kubrick is making viewers aware of the environment that man’s early ancestors inhabited, including the limited food and water and danger of natural predators.

A bit further in the scene, the ape-men have an altercation with a rival tribe that forces them to leave their source of water. They retreat to safety and wait out the night in a cave huddled together. When they awake, attentive viewers can immediately tell that something has changed by listening to the sound. Non-diegetic music plays over the introduction of “the monolith,” a recurring and mysterious visual motif throughout 2001. Unlike what each frame has contained until this point, the monolith, with its perfectly straight lines and smooth surface, is clearly not something made by nature.

A quick cut takes back to more establishing shots of the landscape, and then the camera homes in on the ape pack’s leader as he makes a new discovery. As the film’s iconic soundtrack booms once again, we see the creature learn how to use a large animal bone as a weapon. He fiddles around with it and realizes it can be used as a tool. Several slow-motion shots, both of the ape as a whole and just his swinging arm, depict the thrashing of the bone into other objects. Other animal skeletons fly towards the camera, and live animals fall to their death. The environment has not changed, but the man-apes have now learned how to conquer it.

2001: A Space Odyssey’s story is about many different things: our evolution, our discovery of tools, how we instantly turned those tools into weapons, and, as will become apparent in the latter half when the rouge AI HAL 9000 kills the spaceship crew, how we eventually lose control of our tools. When humanity reaches space, Kubrick shows them learning to walk, eat, and use the bathroom. In a way, they have become like the ape-men once again.

Again, this is all with sparse dialogue. The sound design elevates this movie. From the repeated composition that blares during crucial moments to the isolated breathing in outer space, Kubrick is a master at evoking emotions through the imagery and sounds present, leaving words behind.

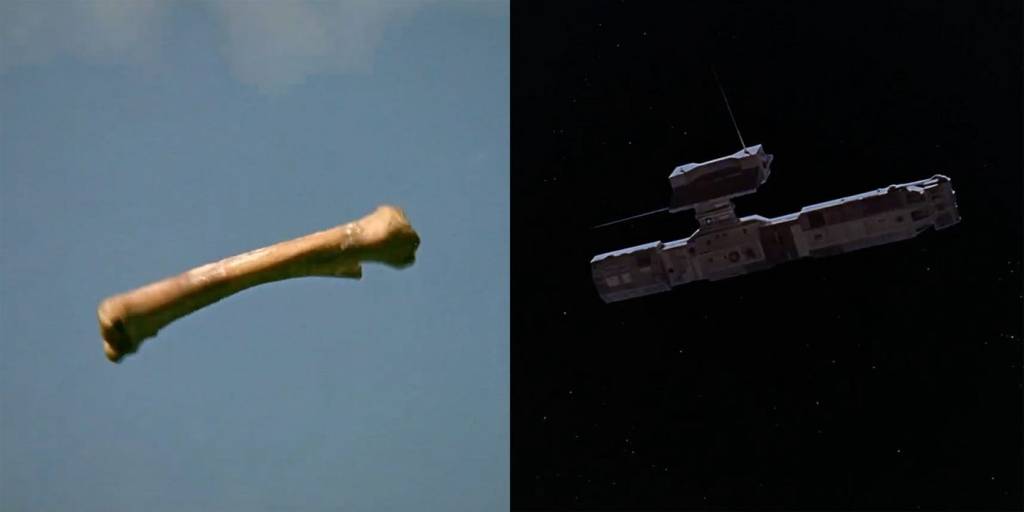

This is the cinematic language that remains present throughout the film’s nearly three-hour runtime. The story’s depth is told with subtlety, rewarding a close reading. The transition from ‘The Dawn of Man’ scene to the rest of the film makes this clear – all of this is connected. The ape-men begin to walk on two legs, scare another group, and the leader kills one of them with his bone weapon. He throws the bone into the air – a close-up shot – and one of the most famous edits in history occurs. A match cut throws viewers to an advanced satellite in space millions of years in the future positioned in the same direction as the bone was.

According to Arthur C. Clark, the satellite is “supposed to be an orbiting space bomb, a weapon in space.” Therefore, the transition from the prehistoric era to the distant future is tethered by the notion that human evolution is connected to the evolution of destruction. Technology may advance, our species may evolve, but we still have the same blood-hungry psyche. All this is expressed visually, pushing the boundaries of film as an art form.

Even when 2001’s scenes are confusing and not as straight forward, Kubrick still imbues each frame with a sense of awe. Take, for example, the journey’s final twenty minutes. Dave Bowman (Keir Dullea), the protagonist and mission commander of the Discovery 1 ship, is sucked into some sort of wormhole. Kubrick presents a psychedelic sequence of flashing colors and shaky camera as Dave enters this star gate. Next thing we know, Dave is in an eerie room. Perhaps a sterile cage of sorts, as if something is observing him. In a series of cuts, he ages dramatically, before finally, the monolith appears again. It is the same peculiar object from ‘The Dawn of Man.’ A frail, old, and pale Dave reaches his hand toward it. Dave passes away, but is reincarnated as a ‘star child’ – some sort of energy being that resembles a newborn infant.

We see the star child looking down at planet Earth and the rest of the galaxy. It’s a new dawn; the birth of an entity that doesn’t need technological devices to survive in uncharted space. While critics and scholars have debated the meaning of the imagery, its clear that Kubrick is connecting this ending to the ape-men of yore. Just as the film opens with ancient life, the film closes with new life and humanity’s possible next chapter with rich possibilities ahead of it. And it does so all without dialogue.

In How Movies Work, author Bruce Kawin writes that a scene is like a theatrical act, and each act must “carry the story through a major phase of the action… bringing dramatic elements into focus.” In 2001: A Space Odyssey, truly no scene is wasted. Each sequence gives viewers so much to unpack and dissect. In this magnum opus, Kubrick showed how much a filmmaker can accomplish with just the visual parts of the film medium.